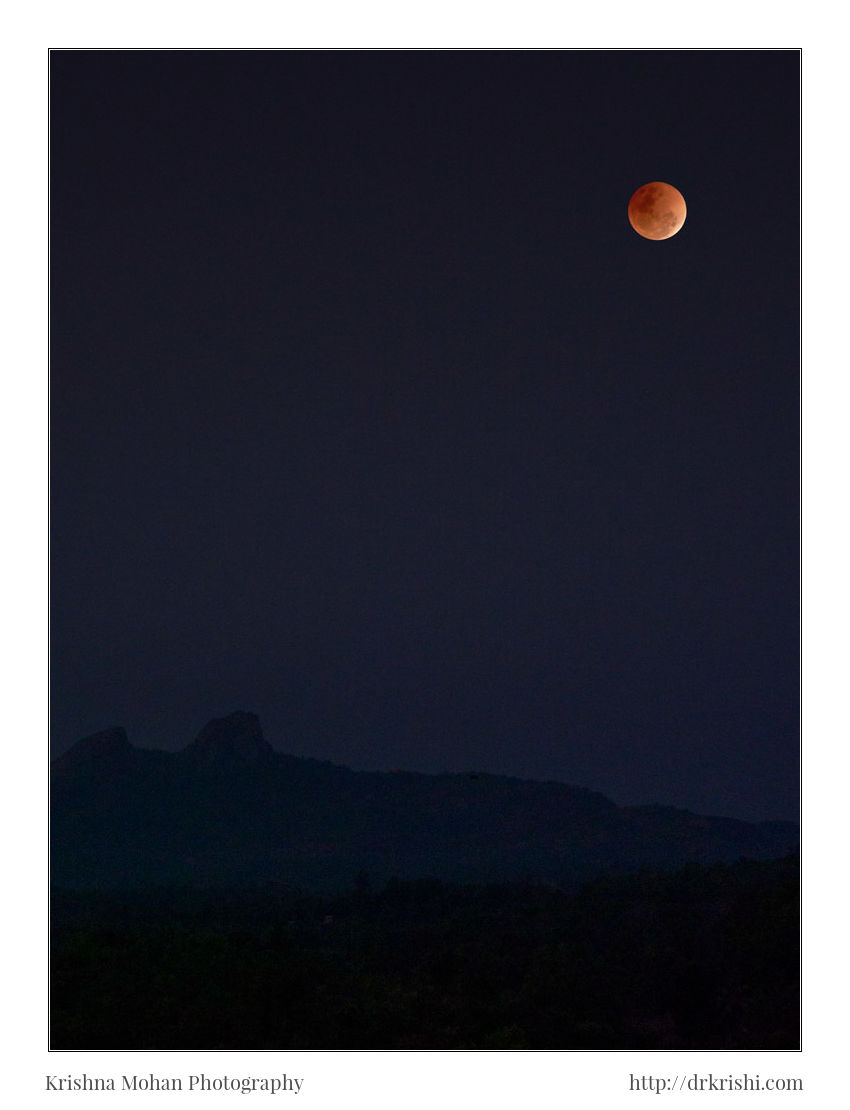

We in India witnessed the Super Blue Blood Moon 2018 eclipse during moon rise on the evening of January 31st, 2018. I used two lenses to capture the eclipse. Olympus M.Zuiko Digital ED 12-100mm f/4 IS PRO Lens & Olympus 300mm f/4 IS PRO M.Zuiko Digital ED Lens on Olympus OMD EM1 Mark II body. I chose an area called Kodangallu near my hometown Moodabidri. The large rocky outcrop at Kodangallu where I was standing has a monument called Nyaya Basadi which was at elevation and gave a clear view of Konaje Kallu on the east. Konaje Kallu is two large stony outcrop which is visible from the sky and was earlier used as a pointer towards the Mangalore airport. It was then named by pilots as Ass’s ears.

When I reached Kodangallu to photograph moon, Sun was just setting behind us as large amber globe. Haze was quite a lot and I was able to see the moon rising from the horizon in my google sky map but was unable to spot in the sky. The eclipsed moon was totally invisible. I was able to see the moon at around 6 degrees above the horizon as the total eclipse started receding at around 7:26 PM.

I used live view with magnification to accurately acquire focus on the moon surface. I have used this trick many times for my moon photography and it works great! Bracketing few shots would be nice so that you can get an accurately exposed moon. The metering for the moon is quite tricky. As it is a bright object in a dark sky. Spot metering will be your friend in shooting the moon. If your camera has it, use it while metering off the moon. Experiment with bracketing to bring out other objects in the frame. It’s better to have the foreground a little dark than the moon is completely blown out with no detail.

At around 7:20 PM we could spot the end of total eclipse and as the earth’s shadow passes across the face of the moon, we could spot the moon nicely. The composite you see is the result of several captures stacked on one another to show you the result of the eclipse as it evolved. I had to leave the place at 8 PM due to prior appointment. I also took another capture which you can see above showing the Konaje kallu and the moon. This is also a composite of two different exposure one made for the moon and one for the background and fused together in Photoshop.

A super-blue-blood-moon-and-total-lunar-eclipse combo hasn’t happened in more than 150 years. Even separately, these events are rare. For instance, a blue moon happens when two full moons occur within the same calendar month. Normally, Earth has 12 full moons per year, which equates to one per month. But because the lunar month — the time between two new moons — averages 29.530589 days, which is shorter than most months (with the exception of February), some years have 13 full moons.

Blue moons happen once every 2.7 years, which explains why the last one happened on July 31, 2015. But despite their name, blue moons don’t actually appear blue. A bluish tint is only possible when smoke or ash from a large fire or volcanic eruption gets into the atmosphere. These fine particles can scatter blue light and make the moon appear blue.

Supermoons, however, are more common than blue moons. A supermoon happens when a full moon is at or near perigee, the point in the moon’s monthly orbit when it’s closest to Earth. Because they’re marginally closer to Earth, supermoons can appear up to 14 percent larger and up to 30 percent brighter than regular full moons.

The most recent supermoon happened this past New Year’s Day, on Jan. 1, 2018. The full moon on 31st will be January’s second full moon, it has earned the title of “Super blue moon.”

Finally, the last two events — the total lunar eclipse and the blood moon — are linked. A total lunar eclipse can happen only when the sun, Earth and full moon are perfectly lined up, in that order. With this alignment, the full moon is completely covered in Earth’s shadow.

During a total lunar eclipse, the moon may appear “blood red,” or at least ruddy brown. The Moon does not have any light of its own—it shines because its surface reflects sunlight. During a total lunar eclipse, the Earth moves between the Sun and the Moon and cuts off the Moon’s light supply. When this happens, the surface of the Moon takes on a reddish glow instead of going completely dark.

The red colour of a totally eclipsed Moon has prompted many people in recent years to refer to total lunar eclipses as Blood Moons. The reason why the Moon takes on a reddish colour during totality is a phenomenon called Rayleigh scattering. It is the same mechanism responsible for causing colourful sunrises and sunsets and the sky to look blue. Even though sunlight may look white to human eyes, it is actually composed of different colours. These colours are visible through a prism or in a rainbow. Colors towards the red spectrum have longer wavelengths and lower frequencies compared to colours towards the violet spectrum which have shorter wavelengths and higher frequencies.

The next piece of the puzzle of why a totally eclipsed Moon turns red is the Earth’s atmosphere. The layer of air surrounding our planet is made up of different gases, water droplets, and dust particles. When sunlight entering the Earth’s atmosphere strikes the particles that are smaller than the light’s wavelength, it gets scattered into different directions. Not all colours in the light spectrum, however, are equally scattered. Colors with shorter wavelengths, especially the violet and blue colours, are scattered more strongly, so they are removed from the sunlight before it hits the surface of the Moon during a lunar eclipse. Those with longer wavelengths, like red and orange, pass through the atmosphere. This red-orange light is then bent or refracted around Earth, hitting the surface of the Moon and giving it the reddish-orange glow that total lunar eclipses are famous for.

Fun fact: If you were lucky enough to see a total lunar eclipse from the Moon, you’d see a red ring around the Earth. In effect, you’ll be seeing all the sunrises and sunsets taking place at that specific moment on Earth!