Nearly all the greatest work is being, and has always been done, by those who are following photography for the love of it…” Alfred Stieglitz

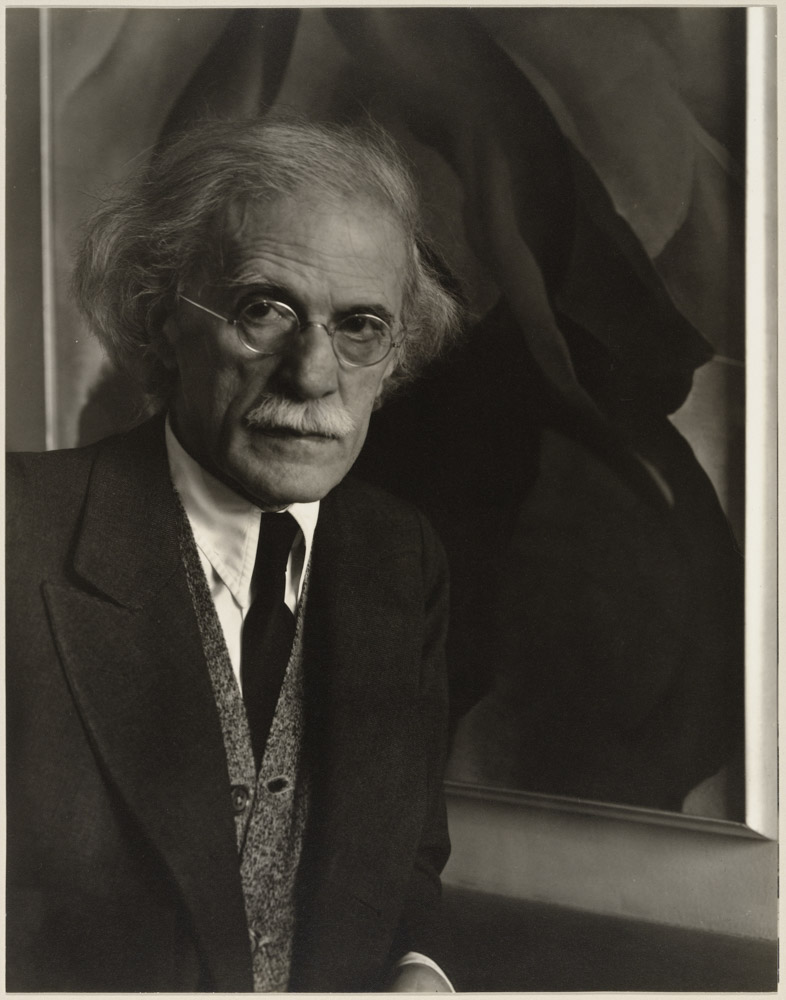

Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) is perhaps the most important figure in the history of visual arts in America. Through his many roles – as a photographer, as a discoverer and promoter of photographers and of artists in other media, and as a publisher, patron, and collector – he had a greater impact on American art than any other person has had.

First, in this series of article on great masters of photography, I will be exploring Alfred Stieglitz’s works along with examples and his quotes which in turn helps us to understand his work better. This series has a selfish goal. I am doing this for my own understanding of craft than anything else. If you like such a series, please comment below. I will be coming with several more on a monthly basis.

“…the goal of art was the vital expression of self.” – Alfred Stieglitz

An ambitious photographer, writer, and entrepreneur, Alfred Stieglitz had a tremendous impact on early 20th-Century art. Founder of the influential “291” gallery on Fifth Avenue, he helped in the exposure of American audiences to European avant-garde painting and sculpture. He tirelessly promoted the first distinctly American flavours of Modern art. Alfred Stieglitz put his entire life on the line to help promote photography and to elevate photography to the status of Art.

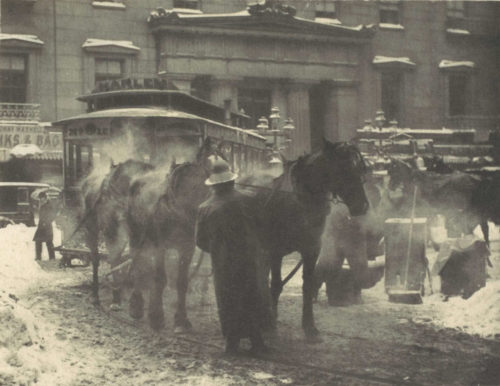

Talking about his work, The Terminal, 1892 he said “From 1893 to 1895 I often walked the streets of New York downtown, near the East River, taking my hand camera with me. . . . [One day] I found myself in front of the old Post Office. . . . It was extremely cold. Snow lay on the ground. A driver in a rubber coat was watering his steaming car horses.”

Though many of Alfred Stieglitz’s early photographs relied heavily upon atmosphere to mute the harshness of urban life, he romanticized nothing in this image. At the southern end of the Harlem streetcar line that travelled up and down Fifth Avenue, he simply captured a streetcar driver watering his horses in front of the old Post Office.

At the time, Stieglitz had just returned from Germany and found America culturally barren in comparison. According to one anecdote, when he saw the horses being nourished by their driver, he decided that he should assume the same role and nourish the arts in this country. Within a few years, Stieglitz was organizing pioneering exhibitions of painting, photography, and sculpture in his modest galleries.

He was, necessarily, a passionate, complex, driven and highly contradictory character, both prophet and martyr. The ultimate maverick, he inspired great love and great hatred in equal measure.

Stieglitz’s spent a huge amount of time and effort in making the final prints. Patience was necessary at all stages: setting up the scene, working with the negative, making the print. Stieglitz himself told the story of Winter, Fifth Avenue, the picture above, this way:

“On Washington’s birthday in 1893, a great blizzard raged in New York. I stood on a corner of Fifth Avenue, watching the lumbering stagecoaches appear through the blinding snow and move northward on the avenue. The question formed itself: could what I was experiencing, seeing, be put down with the slot plates and lenses available? The light was dim. Knowing that where there is light, one can photograph, I decided to make an exposure. After three hours of standing in the blinding snow, I saw the stagecoach come struggling up the street with the driver lashing his horses onward. At that point, I was nearly out of my head, but I got the exposure I wanted.”

“Photography my passion, the search for truth, my obsession.” – Alfred Stieglitz

Stieglitz was born in Hoboken, New Jersey, but spent the better part of his education in Germany, where he trained as a mechanical engineer. While abroad, he began taking photography seriously, entering his work in competitions and showing in magazines. In 1890, Stieglitz returned to America and began making a name for himself, first as an editor for The American Amateur Photographer, and later as an organizer of the Camera Club of New York. During his time with the Camera Club, Stieglitz used its publication, Camera Notes, to advance his ideas about photography.

Stieglitz resurrected Renaissance attitudes about artistic craft and genius and applied them to photography; satisfactory results were designated “Pictorial” photographs. In 1902, referencing earlier artist secessions in Munich and Vienna, he organized an exhibition of photographs under the title, “The Photo-Secession,” at the National Arts Club. The show aimed to defend Pictorial photography as a viable art form in response to the avalanche of poorly composed snaps, hackneyed clichés, and slapdash processing efforts tarnishing the medium.

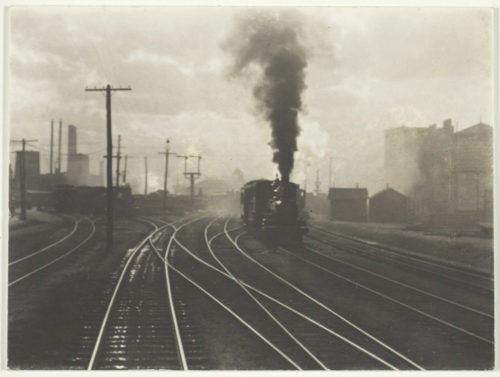

The Hand of Man was first published in January 1903 in the inaugural issue of Camera Work. With this image of a lone locomotive chugging through the train yards of Long Island City, Stieglitz showed that a gritty urban landscape could have an atmospheric beauty and a symbolic value as potent as those of an unspoiled natural landscape. The title alludes to this modern transformation of the landscape and also perhaps to photography itself as a mechanical process. Stieglitz believed that a mechanical instrument such as the camera could be transformed into a tool for creating art when guided by the hand and sensibility of an artist. The Hand of Man pay homage to the hazy aesthetic and urban fascination of the Impressionists (compare: Monet’s La Gare Saint-Lazare, 1877). The use of photogravure and lush paper as means of presenting photographs in Camera Work further added to their visual and tactile appeal.

Stieglitz’s new publication, Camera Work became the aesthetic and theoretical touchstone of the Pictorialists. In 1905, Edward Steichen, a colleague and future curator of the photography department at the Museum of Modern Art, offered his studio as an exhibition space to Stieglitz, giving rise to the “Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession.” Space acted as a complement to the pages of Camera Work, allowing visitors to experience Pictorialist photography in a gallery setting.

Stieglitz’s early work reveals a keen awareness of European painting. His aesthetic evolved over time. The clean edges and sharp focus of his “straight” photographs stand in contrast to the sketchy style that first characterized the Pictorialists. Nevertheless, his commitment to the formal and expressive potential of the medium remained. Despite its historical subject, the formal concerns expressed by Stieglitz share much more in common with contemporary avant-garde painting than documentary photography. Unsurprisingly, it was around this time that “The Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession” was renamed 291, and Stieglitz began incrementally dedicating more space and time to presenting European painting and sculpture.

“The ability to make a truly artistic photograph is not acquired off-hand, but is the result of an artistic instinct coupled with years of labour.” – Alfred Stieglitz

A decade earlier, two savvy businessmen in Rochester, George Eastman and Henry A. Strong had formed a company that would transform the face of photography forever: The Eastman Dry Plate Company (later Eastman Kodak). In response to the proliferation of cameras, “easily operated by any schoolboy or girl,” Stieglitz set to work distinguishing his photographic vision from the snapshots of the unwashed masses.

“Photography is not an art. Neither is painting, nor sculpture, literature or music. They are only different media for the individual to express his aesthetic feelings… You do not have to be a painter or a sculptor to be an artist. You may be a shoemaker. You may be creative as such. And, if so, you are a greater artist than the majority of the painters whose work is shown in the art galleries of today.” – Alfred Stieglitz

The Steerage appeared in Camera Work for the first time in 1911, the same year that Stieglitz organized Picasso’s first solo show in America. The Steerage, a photograph taken by Alfred Stieglitz in 1907. It has been hailed as one of the greatest photographs of all time because it captures in a single image both a formative document of its time and one of the first works of artistic modernism. Reflecting upon this iconic image, Stieglitz wrote:

“A round straw hat, the funnel leading out, the stairway leaning right, the white drawbridge with its railings made of circular chains—white suspenders crossing on the back of a man in the steerage below, round shapes of iron machinery, a mast cutting into the sky, making a triangular shape. I stood spellbound for a while, looking and looking. Could I photograph what I felt, looking and looking and still looking? I saw shapes related to each other. I saw a picture of shapes and underlying that the feeling I had about life.”

In his account for The Steerage, Stieglitz calls attention to one of the contradictions of photography: its ability to provide more than just an abstract interpretation, too. The Steerage is not only about the “significant form” of shapes, forms and textures, but it also conveys a message about its subjects, immigrants who were rejected at Ellis Island, or who were returning to their old country to see relatives and perhaps to encourage others to return to the United States with them.

The three classes of photographers we even see in the present generation —the ignorant, the purely technical, and the artistic used to haunt Stieglitz too.

“In the photographic world today, there are recognized but three classes of photographers—the ignorant, the purely technical, and the artistic. To the pursuit, the first bring nothing but what is not desirable; the second a purely technical education obtained after years of study; and the third brings the feeling and inspiration of the artist, to which is added afterwards the purely technical knowledge. This class devote the best part of their lives to the work, and it is only after an intimate acquaintance with them and their productions that the casual observer comes to realize the fact that the ability to make a truly artistic photograph is not acquired off-hand, but is the result of an artistic instinct coupled with years of labour. ” – Alfred Stieglitz

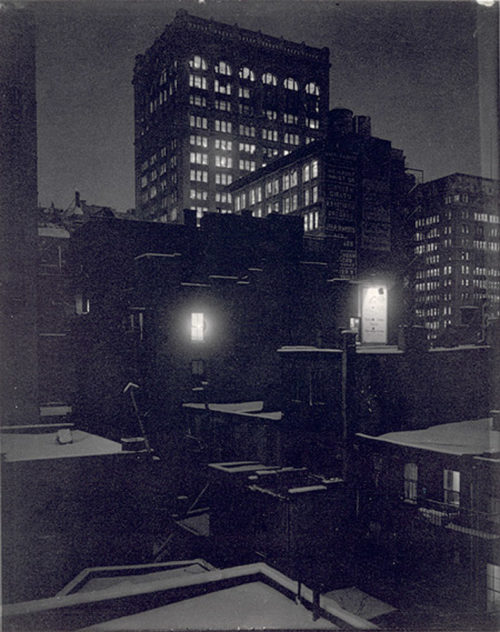

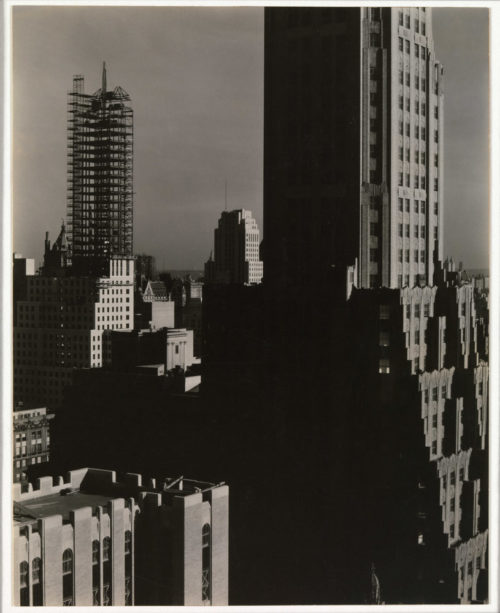

At the turn of the century, Stieglitz’s duties as gallery owner, publisher, editor, and promoter left him little time to photograph. When the mood struck him, however, which began to happen with some frequency about 1915, he did not look far afield but photographed his colleagues at the gallery and the view from his window with a modernist rigour exceeded only by Strand.

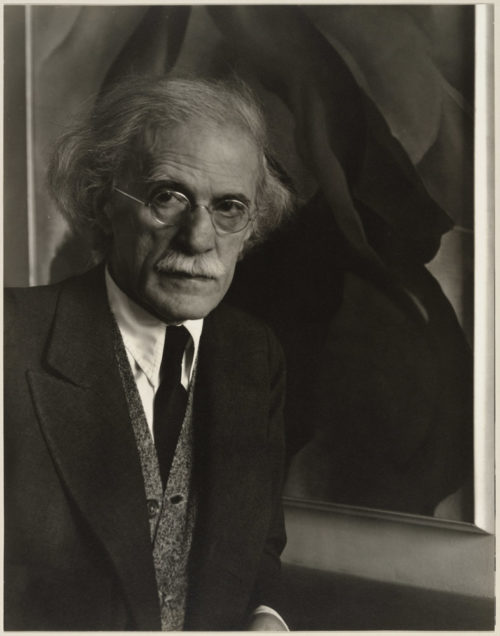

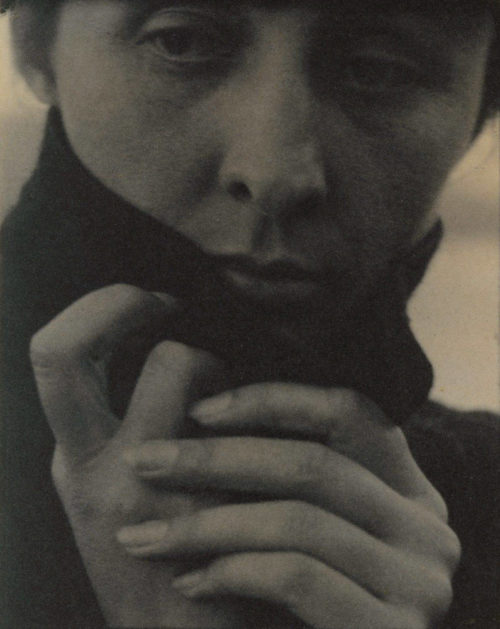

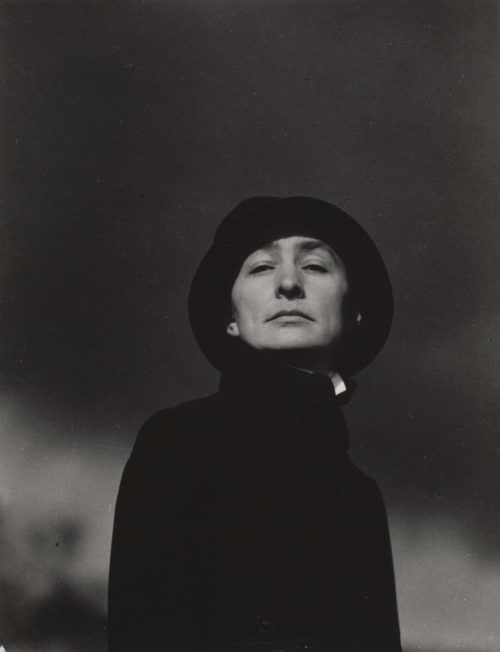

In 1916, Stieglitz found a muse and future wife in the painter, Georgia O’Keeffe. Inspired by his new infatuation, his work began to take a figurative turn. Over the years, he created hundreds of photographs of O’Keeffe, whom he felt could not be adequately represented in a single image.

O’Keeffe’s arrival in New York marked the beginning of her romantic relationship with Alfred Stieglitz. Their relationship grew stronger as a result of their mutual love for art and interaction between their respective arts. Already a famous photographer, Stieglitz started photographing O’Keeffe and would eventually produce about 300 portraits of her between 1918 and 1937. One photography session, in particular, brought them closer together. Stieglitz had invited Georgia to his apartment while his wife, Emmeline, was shopping. He proceeded to take several nude photographs of Georgia, but their session was interrupted by the return of Emmeline, who was enraged and demanded that Stieglitz move out of the apartment. His marriage with Emmeline had always been strained: he was not interested in what he saw as her superficial social aspirations in elite society, and she never mixed with his artist colleagues. Therefore, the break was somewhat of a relief for Stieglitz, who had felt restricted under his wife’s domain. With Georgia, he shared a passion for art and a persistent sexual drive, which presented itself in both of their works.

Stieglitz assisted O’Keeffe in establishing her artistic career by organizing exhibits and selling her artwork at soaring prices. As a result, her reputation flourished, and her relationship with Stieglitz deepened. After Stieglitz’s first wife divorced him in 1924, O’Keeffe reluctantly agreed to marry him. Although she did not feel the need to get married, he insisted on it. However, O’Keeffe kept her own name, and their life as a married couple was far from conventional.

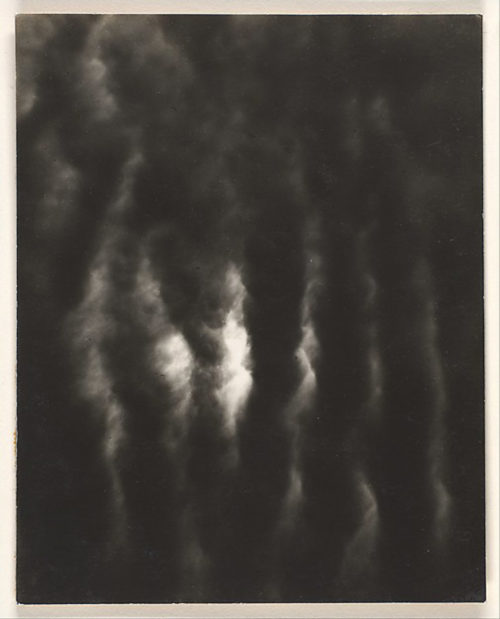

With the title of his 1922 series of photographs, Music, Stieglitz cued viewers to understand his photographs as expressive of nature yet free from its literal representation. Clouds, natural in origin and abstract in appearance, provided the perfect vehicle for his artistic quest. In Music No. 1, they collect and hover like unresolved chords over Stieglitz’s country home, which itself is rendered as a triad glowing in the darkening landscape.

“I have always been a great believer in today. Most people live either in the past or in the future so that they really never live at all. So many people are busy worrying about the future of art or society, they have no time to preserve what is. Utopia is at the moment. Not in some future time, some other place, but in the here and now, or else it is nowhere.” – Alfred Stieglitz

“For that is the power of the camera: seize the familiar and give it new meanings, a special significance by the mark of a personality.” – Alfred Stieglitz

Stieglitz took at least 220 photographs that he called Equivalent or Equivalents; all feature clouds in the sky. The majority of them show only the sky without any horizon, buildings or other objects in the frame, but a small number do include hills or trees. One series from 1927 prominently features poplar trees in the foreground. Almost all of the photographs are printed very darkly so the sky often appears black or nearly black. The contrast between the sky and the much lighter clouds is striking in all but a few of the prints. Some images include the sun either as a distinct element in the photograph or as an illuminating force behind the clouds.

Stieglitz continued photographing clouds and skies for most of the next decade. In 1925 he began referring to these photographs as Equivalents, a name he used for all such photographs taken from that year forward. In 1929 he renamed some of the original Songs of the Sky as Equivalents, and these prints are still known by both names today.

Dorothy Norman once recorded a conversation between Stieglitz and a man looking at one of his Equivalents prints:

- Man (looking at a Stieglitz Equivalent): Is this a photograph of water?

- Stieglitz: What difference does it make of what it is a photograph?

- Man: But is it a photograph of water?

- Stieglitz: I tell you it does not matter.

- Man: Well, then, is it a picture of the sky?

- Stieglitz: It happens to be a picture of the sky. But I cannot understand why that is of any importance.

Stieglitz certainly knew what he had achieved in these pictures. Writing about his Equivalents to Hart Crane, he declared: “I know exactly what I have photographed. I know I have done something that has never been done…I also know that there is more of the really abstract in some ‘representation’ than in most of the dead representations of the so-called abstract so fashionable now.”

The Equivalents are sometimes recognized as the first intentionally abstract photographs, although this claim may be difficult to uphold given Alvin Langdon Coburn’s Vortographs that was created almost a decade earlier. Nonetheless, it is difficult to look at them today and understand the impact that they had at the time. When they first appeared photography had been generally recognized as a distinct art form for no more than fifteen years, and until Stieglitz introduced his cloud photos there was no tradition of photographing something that was not recognizable in both form and content.

Photographer Ansel Adams said Stieglitz’s work had a profound influence on him. In 1948 he claimed his first “intense experience in photography” was seeing many of the Equivalents (probably for the first time in 1933, when they met)

In the time of Alfred Stieglitz, photographers were obsessed with making their photos look like paintings and other forms of “real art.” Stieglitz proposed something else: make your photos look like photos. A lot of photographers during the time of Stieglitz used fancy techniques and methods to blur their photos, obscure them, and make them look more like paintings or conceptual art. Stieglitz encouraged many photographers to have pride in their work:

“My aim is increasingly to make my photographs look so much like photographs [rather than paintings, etchings, etc.] that unless one has eyes and sees, they won’t be seen – and still, everyone will never forget having once looked at them.” – Alfred Stieglitz

“Photographers must learn not to be ashamed to have their photographs look like photographs.” – Alfred Stieglitz

“I do not object to retouching, dodging. or accentuation as long as they do not interfere with the natural qualities of photographic technique.” – Alfred Stieglitz

Most of us get dissuaded if someone calls our good photography work as amateurish. But Stieglitz was of a different opinion. He loved amateur. He felt just because you are a professional doesn’t mean you’re a good photographer. You can take cliché photos and make a living from it, yet all those photos aren’t very interesting.

“Let me here call attention to one of the most universally popular mistakes that have to do with photography – that of classing supposedly excellent work as professional, and using the term amateur to convey the idea of immature productions and to excuse atrociously poor photographs. As a matter of fact, nearly all the greatest work is being and has always been done, by those who are following photography for the love of it, and not merely for financial reasons. As the name implies, an amateur is one who works for love; and viewed in this light the incorrectness of the popular classification is readily apparent.” – Alfred Stieglitz

Over the fifty-years of promoting photography as modern art Stieglitz earned the reputation of being the “godfather of modern photography’, a Renaissance man who had his share of love and lovers throughout his life. In 1946, at the age of 82, Stieglitz suffered a fatal stroke. Stieglitz’s career provides a visual and textual foundation for those interested in the intersections of photography, Art, and Modernity. His work and passion continue to inspire artists to this day.

Check this Biography of Alfred Stieglitz – Alfred Stieglitz: The Eloquent Eye, By PBS aired 16 April 2001

[youtube]PNn6H4SEgQc[/youtube]

All photos in this article © 2019 Estate of Alfred Stieglitz / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Reference:

Alfred Stieglitz: Taking Pictures, Making Painters Book by Phyllis Rose 2019 Yale University Press.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_Stieglitz

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camera_Work#Issues_and_contents

Focus On: Alfred Stieglitz By Cory Rice

Stieglitz, The Steerage Khan Academy

The Steerage and Alfred Stieglitz by Jason Francisco (Author), Elizabeth Anne McCauley (Author) March 2012

8 Lessons Alfred Stieglitz Can Teach You – Eric Kim Photography