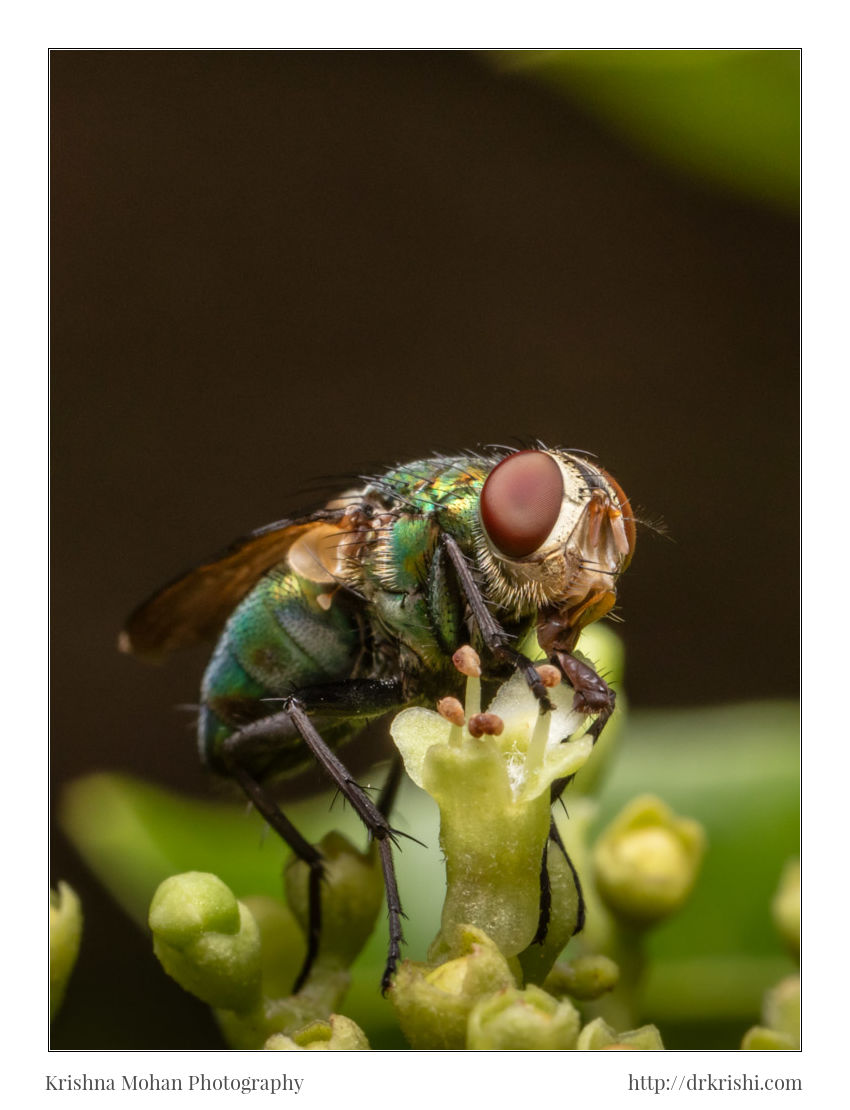

At Sammilan Shetty Butterfly Park at Belvai, I captured this common green bottle fly feeding on flowers using Canon EOS 5DS R DSLR with Canon MP-E 65mm f/2.8 1-5x Macro when I was doing Canon EOS 5DS R Review

The common green bottle fly (Lucilia species) is a blow fly found in most areas of the world, and the most well-known of the numerous green bottle fly species. It is 10-14 mm long, slightly larger than a house fly, and has brilliant, metallic, blue-green or golden coloration with black markings. It has short, sparse black bristles (setae) and three cross-grooves on the thorax. The wings are clear with light brown veins, and the legs and antennae are black. The maggots (larvae) of the fly are used for maggot therapy.

Common green bottle fly is common all over the temperate and tropical regions of the planet. It prefers warm and moist climates and accordingly is especially common in coastal regions, but it also is present in arid areas. The female lays her eggs in meat, fish, animal corpses, infected wounds of humans or animals, and excrement. The larvae feed on decomposing tissue. The insect favours domestic sheep. This can lead to blow fly strike, causing problems for sheep farmers.

The life cycle of Lucilia is typical of flies in the family Calliphoridae in that the egg hatches into a larva that passes through three instars, enters a prepupal and then a pupal stage before emerging into the adult stage or imago. The female lays a mass of eggs in a wound, a carcass or corpse, or in necrotic or decaying tissue. The eggs hatch in about 9 hours in warm, moist weather, but may take as long as three days in cooler weather. In this, they differ from the more opportunistic Sarcophagidae, that lay hatching eggs or completely hatched larvae. A single female Lucilia typically lays 150?200 eggs per clutch and may produce 2,000 to 3,000 eggs in her lifetime. The pale yellow or grayish, conical larvae, like those of most blow flies, have two posterior spiracles through which they respire. These larvae are moderately sized, ranging from 10 to 14 millimeters long.

The larva feeds on dead or necrotic tissue for 3 to 10 days, depending on temperature and the quality of the food. During this period the larva passes through three larval instars. At a temperature of 16°C, the first larval instar lasts about 53 hours, the second about 42 hours and the third about 98 hours. At higher temperatures (27°C) the first larval instar lasts about 31 hours, the second about 12 hours, and the third about 40 hours. Third-instar larvae then drop off the host onto soil, where available, where they enter a pupal stage which usually lasts from 6 to 14 days. However, if the temperature is suitably low, a pupa might overwinter in the soil until the temperature rises. After emerging from the pupa, the adult feeds opportunistically on nectar or other suitable food, such as carrion, while it matures. Adults usually lay eggs about 2 weeks after they emerge. Their total lifecycle typically ranges from 2 to 3 weeks, but this varies with seasonal and other circumstances.

Lucilia is an important species to forensic entomologists. The stage of its development on a corpse is used to calculate a minimum postmortem interval, so that it can be used to aid in determining the time of death of the victim. The presence or absence of Lucilia can provide information about the conditions of the corpse. If the insects seem to be on the path of their normal development, the corpse likely has been undisturbed. If, however, the insect shows signs of a disturbed life-cycle, or is absent from a decaying body, this suggests postmortem tampering with the body. Because Lucilia is one of the first insects to colonize a corpse, it is preferred to many other species in determining an approximate time of colonization. Developmental progress is determined with relative accuracy by measuring the length and weight of larval life-cycles.

Lucilia sericata has been of medical importance since 1826, when Meigen removed larvae from the eyes and facial cavities of a human patient. L. sericata has shown promise in three separate clinical approaches. First, larvae have been shown to debride wounds with extremely low probability of myiasis upon clinical application. Larval secretions have been shown to help in tissue regeneration. L. sericata has also been shown to lower bacteremia levels in patients infected with MRSA. Basically, L. sericata larvae can be used as biosurgery agents in cases where antibiotics and surgery are impractical. Larval therapy of L. sericata is highly recommended for the treatment of wounds infected with Gram-positive bacteria, yet is not as effective for wounds infected with Gram-negative bacteria.

This is yet another informative article sir 🙂